|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

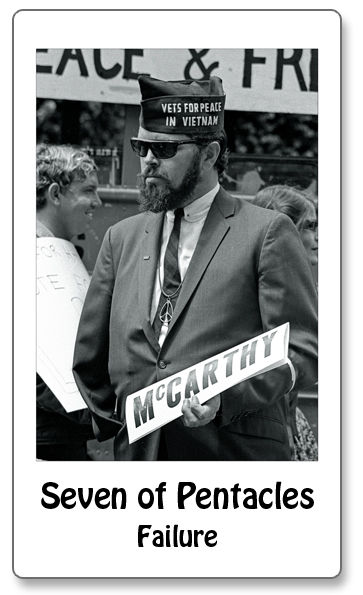

SEVEN OF PENTACLES "With our combat methods everything in our people's hands can be turned into a weapon against the enemy, even a stick, a carrying pole or a heap of stones. With the rudimentary weapons used very skillfully, cleverly, and widely, we have caused heavy losses to the GIs. And it is only natural that these American 'playboys' dread the spiked pits and booby traps laid by our guerillas and people, into which they fall everyday." --from "Vietnamese Studies," Vol. 20, one of a series of pamphlets written and issued in the 60s to the Viet Cong and edited by North Vietnamese war strategist Nguyen Khac Vien A Vietnam veteran stands in patient witness during a 1968 war protest. He draws attention with a smart suit and tie; his coat sleeve pinned up to accommodate the shadow of a missing right arm. His patience is that of the Seven of Pentacles, often pictured as the watchful farmer leaning on a shovel beside a flowering bush. He waits. What will be reaped from what has been sown? In this instance, and in the view of Aleister Crowley who called the Seven the card of failure, there is no hope. "The stake has been thrown down and it has been lost. That is all. Labor itself is abandoned and everything is sunk in sloth." The former soldier is now a witness, but also the flowering bush for other witnesses who must reckon with his wound and the casualties reaped from a futile, seemingly endless war. Since the middle ages, the idea of a Wasteland has been an essential symbol of the despairing myths of failure. Just as careless plantings can produce poor crops, so venal motives can nurture a landscape of spiritual death. In this instance, the Vietnam veteran has returned from one Wasteland only to enter another, from one of grotesquery and death to another of deep cultural anxiety, leaderless and without direction. Ten years after the Vietnam War, Herman Rapaport examined the American soldier's experience in an essay highlighting the collision of realities that created a hell in Vietnam. Rapaport borrowed the concept of a plateau from Gregory Bateson to represent "a level without climax, a development of intensities which never break or crest." This, he said, was embodied in the Viet Cong art of war: to confront the overwhelming firepower of the American military with something anticlimactic. The Viet Cong avoided direct, head-on contact "but at ambush, at the trap, they are devastating." Vietnam was fought without decisive battles and lost to a strategy that could create a devastating weapon from a Coke can, bullet, and nail. "Step on it," writes Rapaport, "and you lose your foot." This landscape of somnambulistic boredom, punctuated by frightful flashes of adrenalin and slaughter, seemed to have no territorial integrity. Rapaport relates the remembrance of a rifleman from the 1st Cavalry Division who, moving into a quiet valley, suddenly hears the Viet Cong yelling through bullhorns, "kill G.I.! kill G.I.!" "An invisible speaking, and then mortar fire into the center of the unit, widening out so that the men cannot hold a perimeter, and the wounded G.I.s crying out, 'Kill me! Kill me!" followed by misdirected ammo drops which the enemy recovers and uses, followed by more wounded, and terrified bystanders with empty clips. And still the steady rain of mortar fire. 'I always had a bad habit of being afraid of wounded guys. A wounded guy crying, I didn't know what to do.' Paralysis, fragmentation, and then just a blur." With no tangible territory to defend, the American soldier in Vietnam still had what Rapaport describes as "one unshakable faith in a defined zone." This was his body. "To lose a leg or a hand or a foot in American society is a most terrible consequence in a society that believes everyone must be whole" says Rapaport, referring to "an ideology that insists libido is only attracted to unities." Indeed, wounded soldiers in Vietnam suffered amputations and paraplegia of the lower extremities at a rate 300 percent higher than soldiers in World War II. The thought of coming back without all of one's organs, especially the genitals, impaired the will of Americans, especially draftees, to fight in the field. Thus, troops would go on "search and avoid" missions that served only to display to the relentless enemy their feckless disinterest in the war's outcome. In this instance, we bow to Crowley's implication of material failure, that of Saturn in Taurus in which the meanest management of the earth's most potent possibilities results in a burned, parched land. This was the Wasteland of Vietnam, filled with Parsifals carrying M-16s on a diffident Grail Quest, and each afraid to raise the crucial question that might cure the King's unmentionable wound, the wound that bound this country to infertility and fire, that left flowers to die on the bush and men to die in the jungles. |