|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

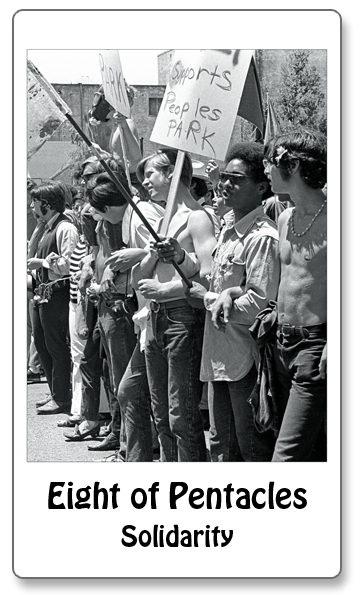

EIGHT OF PENTACLES "We must leave our dreams and abandon our own beliefs and friendships of the time before life began. Let us waste no time in sterile litanies and nauseating mimicry. Leave this Europe where they are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of every one of their streets, in all the corners of the globe. For centuries they have stifled almost the whole of humanity in the name of a so-called spiritual experience. Look at them today swaying between atomic and spiritual disintegration." --Frantz Fanon, "The Wretched of the Earth," 1961 Perhaps the only effective response to failure is to start again. But how do we do this? The Eight of Pentacles with its prudent dedication to learning and discipline suggests one approach. Might it be possible to reconstruct reality? Yes, but not without study and work. Not without new paradigms that have no power until they are proven. This takes time. Two devastating European wars had brought the world to the brink of total human annihilation. Exhausted at the mid-20th century, European powers loosened their colonial grip on what came to be called The Third World, comprising southern non-white nations that for decades (and in some cases centuries) had fed the furnaces of Europe's enriching economies with the sacrifice of their native resources. And to what end? Wealth had not in any way curbed Europe's ethnic grudges, assuaged its class struggles, or inspired peace and conciliation. To the contrary, wealth had bred more struggles, more wars, more devastation, more greed. Yet with Europe's loosened colonial grasp, great new nations arose in the 40s and 50s, notably on the Chinese mainland and the Indian subcontinent, across Africa, along the Indonesian archipelago and throughout the Middle East. A war of liberation in Algeria humbled the French and presaged the American failure in Vietnam. These were not the first or the last to assert what Fanon, an Algerian psychologist turned revolutionary, called "a new history of Man, a history which will have regard to the sometimes prodigious theses which Europe has put forward, but which will also not forget Europe's crimes . . . " And Europe's crimes were noteworthy: racism, barbaric exploitation, and genocide against the world's non-European cultures. Fanon, as a practicing psychologist, applied a diagnosis: European oppression drained from its subjects all the benefits of cultural identity and left them psychotic. It was a diagnosis that greatly influenced feminist therapist Phyllis Chesler's analysis of the "colonialist" condition of contemporary women presented in Women And Madness. The fight against colonialism was essential to the mental health of four-fifths of the world's population. And it was a fight requiring resistance by any means necessary, including violence. Fanon's short life (he died at age 36 of leukemia) cast a seductive mystique over the aspirations of revolutionaries seeking to overthrow colonial hegemony. Fanon was perspicuous in acknowledging the capability of native colonial collaborators to become tyrants and oppressors of their own peoples (what he described as "an oppressed person whose permanent dream is to become the persecutor"). "Every brother on a rooftop," as Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver said, quoted Fanon's words from The Wretched of the Earth. And Cuba's Che Guevara, another hero of the Counterculture resistance, was deeply influenced by Fanon's call for world revolution against the West, as were the Students for A Democratic Society, American civil rights activists, and Sixties political radicals including French Maoists, the Red Army Brigade, and the Weather Underground. The appeal of solidarity with Third World political struggles found a lively resonance among members of the New Left who saw in the colonialist oppression of non-European cultures a global enactment of their own more parochial victimization. How could segregation in the United States not be a direct consequence of Europe's pre-industrial African slave trade? Civil rights activism was a springboard to the awareness of neocolonialism's impacts and their origins within a politically exclusive economic culture. College students who joined civil rights marches had little trouble relating the odious regimentation of their formal educations to the presumed requirements dictated by the nation's captains of industry. Schools, said teacher Jerry Farber in his 1969 book The Student As Nigger, "exploit and enslave students; they petrify society; they make democracy unlikely . . . our schools teach you by pushing you around, by stealing your will and your sense of power, by making timid, square, apathetic slaves out of you . . . " Marching in solidarity, as these 1969 protestors prepared to do, created an empowering feeling of resistance, even as the objects of resistance-capitalists, warlords, college deans, cops, dictators-remained vaguely and idiosyncratically linked in each marcher's mind. Few knew the names of those involved in the business of global profiteering, and fewer still understood how "the system" worked. But the urge was strong to identify with those oppressed by Western capitalism, even from within what Mao called "the belly of the beast," and to rebel against a presumed colonization that threatened to bend their own bodies and minds to the slavish service of banal, lifeless consumerism. |