|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

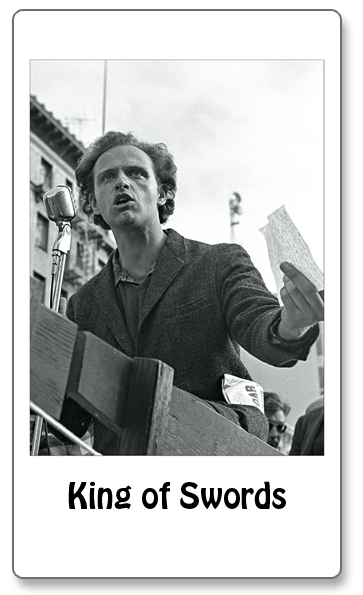

KING OF SWORDS "There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart that you can't take part! You can't even passively take part! And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus - and you've got to make it stop! And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it - that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!" --Free Speech Movement spokesman Mario Savio addressing student supporters before leading 1,500 into UC-Berkeley's administration building for a sit-in to protest university suppression of free speech. December 2, 1964 Like the Queen with her voice, the King of Swords has his words. He is a conscientious steward of the rapiers of reason that in 14 cards have slashed through inspirations and dreams to expose acidulent and underlying truths. It can be dreary work and the King may be excused the lawyerly precision of his arguments and the sometimes obtuse foundations of his thoughts. He can appear as delicate as he is courageous. The Sword King draws his vigor from the resources of infinite mind, since he often lacks the Wands' inspiration, the Cups' charm, and the Pentacles' charisma. It is a quiet, even suppressed, vigor. Among his student colleagues in 1964 a tall, gaunt UC-Berkeley junior named Mario Savio was embraced as a committed civil rights activist, though some thought him a stammering and ineffective speaker. Yet on a warm, fall day of that year Savio took his place as the first student leader of a college revolt, unleashing a thoughtful eloquence that carried the fight for free speech to a Counterculture victory of lasting historic importance. American colleges and universities were traditionally authoritarian, maintaining in loco parentis policies that reduced students to wards of the administration. And in the early Sixties colleges seemed particularly complacent as producers of educated talent to be employed by the nation's expanding corporate economy. UC President Clark Kerr was especially boastful that the multi-campus UC system, which he called a "multi-versity," was engaged in manufacturing college degrees as part of the nation's "knowledge industry." But this paternalism was offensive to many students of the Sixties who were drawn to political activism and resentful of being treated as cogs in a machine. The expression "do not fold, spindle, or mutilate," printed on the ubiquitous computer punch cards required for college registration, became a disparaging phrase students used to describe themselves as components of the university's corporate machinery. It was a theme developed by Savio in his famous Dec. 2 speech as a preamble to a call for action. "We have an autocracy which runs the university," Savio said. Savio would have been the last person to ever take any personal credit for the success of the Free Speech Movement, even though he was the Movement's first and most notable leader. When students began their free speech revolt October 1 by surrounding a campus police car, Savio took off his shoes, climbed onto the roof, and began a dialogue with the crowd. A spontaneous act of non-violence produced an unusually "conversational" rally and, as thousands crowded around the car, Savio elicited a consensus to negotiate with the administration. "He took the audience through his own thinking process, acknowledging his own doubts before arriving at a conclusion." recalled the late Reginald Zelnick, a history student in 1964 and eventually a chairman of the UC-Berkeley history department. "As an historian I always like to remind people that nothing is as beautiful as it appears on the surface. But the FSM was as good as it gets. It certainly never got that good again." Following his Dec. 2 speech on the steps of Sproul Hall, hundreds of students followed Savio into the campus administration center for a non-violent sit-in that would result in nearly 800 student arrests. The action galvanized campus support for the FSM and produced a strong faculty endorsement for free speech. Within a month, a new chancellor at Berkeley had essentially lifted all free speech restrictions on campus. Within a few more months there were student free speech uprisings at UCLA, Harvard, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Columbia. In March, 1965, the University of Wisconsin held the first Teach-In against the Vietnam War, inaugurating a surge of student protest that would escalate into a national force for change. |