|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

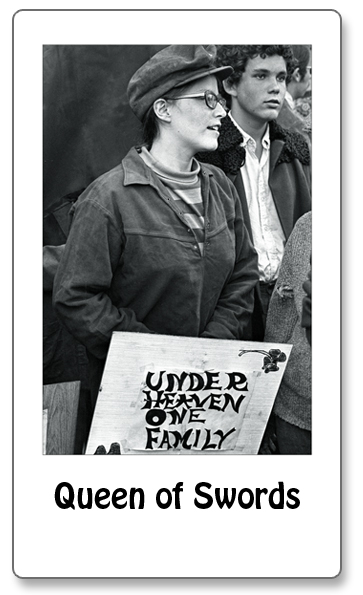

QUEEN OF SWORDS "For most women the psychotherapeutic encounter is just one more instance of an unequal relationship, just one more opportunity to be rewarded for expressing distress and to be "helped" by being (expertly) dominated. Both psychotherapy and marriage isolate women from each other; both emphasize individual rather than collective solutions to women's unhappiness; both are based on a woman's helplessness and dependence on a stronger male authority figure . . . " --Phyllis Chesler, from "Patient and Patriarch: Women in the Psychotherapeutic Relationship" presented to the American Psychological Association, September, 1970 "Women's discovery that to be selfless means not to be in a relationship is revolutionary because it challenges the disconnection from women and the dissociation within women that maintain and are maintained by patriarchy and civilization." --Carol Gilligan, introduction to the 1993 edition of "In A Different Voice" When Phyllis Chesler described in the Sixties how women were being enlisted into careers as psychiatric patients, she exposed a historical link between political oppression and mental illness, a link that extended deeply into family relations. Chesler reported that few women in mental hospitals suffered from psychosis but were actually being treated for individual unhappiness with their feminine roles, no matter how many other female patients (or nonpatients) are similarly unhappy. "Women's inability to adjust to or to be contented by feminine roles has been considered as a deviation from 'natural' female psychology rather than a criticism of such roles," she wrote. Chesler added that both psychotherapy and marriage, the two major socially approved institutions for white, middle class women, function to "save" women through the intervention of an understanding and benevolent male authority. "She wants from a psychotherapist what she wants - and often cannot get - from a husband; attention, understanding, merciful relief, a personal solution - in the arms of the right husband, on the couch of the right therapist. The institutions of therapy and marriage not only mirror each other, they support each other." Chesler's harsh revelations about psychotherapy and women were strongly supported by research that underscored a woman's acute vulnerability in what was supposed to be a therapeutic environment. That some male therapists seemed to have no ethical issue with taking female patients as lovers further aggravated the grievous veracity of Chesler's premise and underscored psychotherapy's prevailing indifference to sexual abuse. Her challenge to the gender-based projections of psychotherapy was widely engaged and brought to light a litany of false therapeutic assessments made by male psychologists about women. These included, of course, the primary value of a vaginal orgasm, but also extended to the acceptance of motherhood as essential to a woman's mental health. It soon became apparent that the practice of patriarchal psychology wasn't about healing a woman's mind as much as it was about controlling her body. Another psychologist, Carol Gilligan, took this discussion farther, hacking with her sword at a 2,000 year-old Western philosophical tradition that had received few contributions from women. Gilligan's work in psychology developed the notion that men and women approach ethical issues differently. Gilligan noted that men addressed moral issues from what she called an ethic of justice, one biased by a search for an abstract universality applicable in all situations and concerned with clear moral choices between right and wrong. Women, on the other hand, tended to address ethical questions from a caring, restorative perspective, and one more focused on the resolution of conflict in relationships than in the application of absolute justice. Gilligan's research led her to describe an "ethic of care" that was distinct from philosophy's dominant ethic of justice as addressed by the two pillars of modern ethical theory, utilitarianism and Kantian ethics. And she concluded that an ethic of care reflected well a woman's focus on personal relationships and emotional consequences, a focus long missing from the cannon of Western thought. Feminist ethics, like feminist psychology, was a sumptuous wellspring of vigorous criticism for both disciplines. In 1926 psychologist Karen Horney wrote, "It is inevitable that the man's position in advantage should cause objective validity to be attributed to his subjective, affective relations to women." Fifty years later a generation of sword queens was having no more of it. If assigned validities were to have any credibility both men and women would provide their attributions. This was the heavy lifting of ideation born from experience that also returns to experience a vivid accounting of new and inescapable realities and that articulates, finally, the unwritten scripts that transform living. |