|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

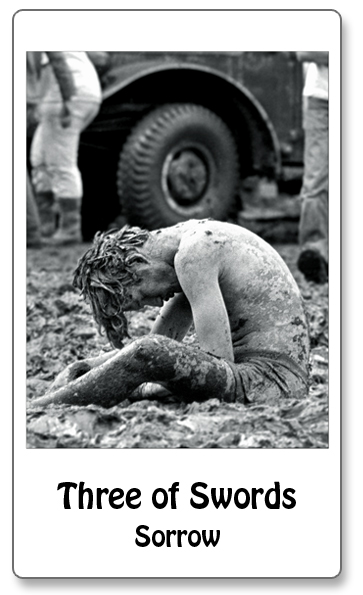

THREE OF SWORDS "Familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. Every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of my ego, seemed to be a wasted effort. A demon had invaded me. I jumped up and screamed, trying to free myself from him . . . my body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying?" --Albert Hoffman, the Swiss researcher who discovered LSD in 1943, describing his reactions while taking the world's first acid trip. "What is so difficult about it is not only the intense fear, the sense of imminent injury or death to yourself, but that you can't get away, you can't avoid it . . . In addition, you've got to somehow keep enough sense about yourself to do what you have to do to prevent it from happening. It's utter terror; when it's over if you survived, the relief is almost impossible to describe." --A young Vietnam War veteran describing his first tour of duty in Eric Bergerund's Vietnam History, "Red Thunder, Tropic Lightning" The Three of Swords introduces what Aleister Crowley calls The Lord of Sorrow. But this is not just any sorrow, certainly not personal disappointment or sadness. It is not even the heartbreaking grief offered through the emotional Cups. Among the captious Swords this is the mind's sorrow: a soul-jarring rupture, a ruthless shock that resets reality. It is a deeper experience that ranges far beyond despair and that changes a life forever; that is, if life survives. It is Weltschmerz. It is the pervading sorrow of irrefutable experience that cannot be forgotten or contained. It is the headache, not the heartache. And it seeps from its source into the cellular structures of friends, families, communities, and the world, perpetually reifying the projections of mortality into every generation's renewed lamentations. Such were war and drugs to the Counterculture generation, agents of sorrow at least as old as the species. Since the deep Bronze Age history has recorded richly disturbing sentiments drawn from the experiences of bloody human warfare. From the dawn of genus homo, humans have reeled from the mind-modifying effects of chemical stimulants and depressants. Both, with their common risk to the functioning and health of the mind, offered harrowing epiphanies to the crucible of Sixties generational passage. Most who ingested or inhaled the drugs of the Sixties did not suffer serious long-term impacts. Most young soldiers who went to fight in Vietnam did not succumb to mental illness. But those who fell on the Tarot's three swords also fell into sorrow's dark chasm in numbers large enough to project a legacy of drug and war-related madness. In the freewheeling atmosphere inspired by San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury, it wasn't long before addictive drugs found a culturally supported niche. "All the amphetamines, or 'speed' - Benzedrine, Dexedrine, and particularly Methedrine - were in far more common use in the late spring than they had been in the early spring" Joan Didion writes in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, her memoir of the Haight in the Sixties. "Where methedrine is in wide use, heroin tends to be available, because, I was told, 'You can get awful damn high shooting crystal, and smack can be used to bring you down.'" Thus, psychedelics were lumped into the company of drugs that, through their addictive qualities, embroider lives with depression and anxiety. Wayne Burton is a college president now, but in the 1960s he was an army officer in Vietnam. On the way to the latrine one morning, he was blown over by a tremendous blast and as he tried to stand up he noticed that body parts were raining down from the sky, landing on his head and shoulders. He approached a black crater, the source of the blast, and was overcome by the sight. "To my right lay a torso heaving one last, reflex-driven sigh. To my left writhed a screaming man clutching the remains of his arm . . . In time two of my men led me to the shower for the first of several I took that day to wash from my body the remnants of corpses that still stain my memory." Burton later learned that it was not an incoming enemy mortar that had caused the carnage. A despondent GI, high on pure heroin, had chosen to commit suicide and take some of his comrades with him. The 18-year-old soldier was cleaning his weapon at a table with five other soldiers when he removed a hand grenade from a box on the table, pulled the pin, and then returned the grenade to the box, detonating its contents. |