|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

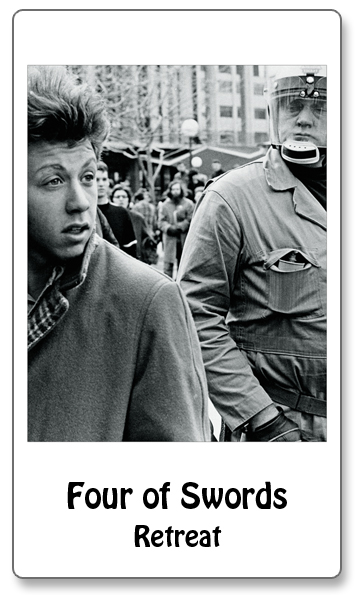

FOUR OF SWORDS "The young seem curiously unappreciative of the society that supports them. 'Don't trust anyone over 30,' is one of their rallying cries. 'Tell it like it is,' conveys an abiding mistrust of what they consider adult deviousness." --Time Magazine, January 6, 1967 The Four of Swords signals a retreat. It is as if what has flown into conflict now falls to earth. There were long pauses on the picket lines of Counterculture resistance. Demonstrating students might chant and march for hours as police looked on. In slow moments each side would consider the other, lines moving and then stopping, stopping and moving. In generational opposition, police stood in for fathers and students stood in for their sons and daughters. It was symbolic of a new relationship between post-war parents and their nearly grown offspring. It marked a retreat of children from parents and, eventually, parents from their children. Anthropologist Margaret Mead was so struck by the evolving generational conflicts of the Sixties that she conceptualized the problem in her 1970 book Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap. Mead visualized three cultural models of generational engagement. In postfigurative cultures the future follows the past. Children learn from their elders everything they need to know because they will inherit their parents' lives. This conservative culture is typical among pre-literate nomads and established agricultural societies. In cofigurative cultures, change has become a dominant force and the future is determined by the present. Youths learn from adults engaged in change and form generational alliances with their peers. Adults and children adapt together to a changing future. Mead described as prefigurative a culture that emerges where change is so rapid that existing cultural systems cannot absorb it. In the whirlwind of sudden change, elders are clueless about the consequences and find that their children, so much closer to the threshold of the future, seem to know much more about its shape and substance. Parents in this culture often learn from their children the direction they will have to take to successfully navigate change. The prefigurative Sixties stretched across the generational poles of authority and rebellion, of freedom and responsibility, of outrage and decorum. Yet the era also sustained a resolute attachment between parents and children, creating dependencies resented by both. They were suddenly two formidable forces in a seesaw battle: parents still pushed the levers, wrote the checks, and controlled the cultural institutions. But their children countered with uncommon energy and fresh, new ideas. But post-war parents were also sentient and sexual humans with dreams, fears and desires. They had their own lives even as they were perturbed (and also intrigued) with the new and insurgent lifestyles of their children. They were drawn to the more freely expressed eroticism displayed by their sons and daughters, eroticism they had helped to inspire through their own comparatively tender and affectionate parenting. They could express sympathy for the civil rights movement and yet feel irrational anxiety about the unknown implications of a racially integrated culture. They were raised not to question authority, especially in a time of war, and perplexed by the implication that their protesting children might be traitors. They were at rest and entrapped in a postfigurative ambivalence, and could resist their children as crudely and inappropriately as their children sometimes rebelled against them. When Alabama Gov. George Wallace threatened to run over student demonstrators who might block the President's limousine, his presidential candidacy received a 20 percent boost in the polls. Following the fatal shooting of Kent State University students by the National Guard, Kent residents . . . including some Kent State parents . . . marched with four fingers raised and chanted "The score is four/And next time more." Cops at the 1968 Democratic Convention were seen vandalizing cars with McCarthy bumper stickers. Mead could see that anything unfamiliar was presumed dangerous to the postfigurative generation that feared "the young are being transformed into strangers before our eyes, that teenagers gathered at a street corner are to be feared like the advance of an invading army." |