|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

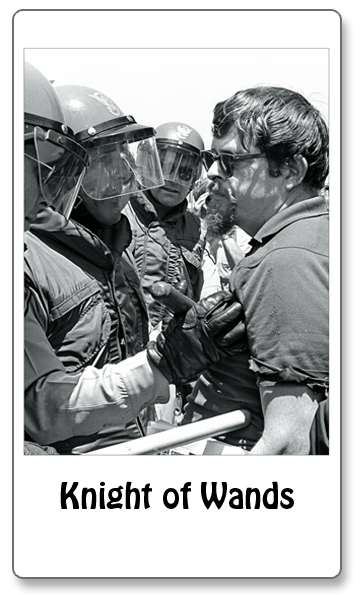

KNIGHT OF WANDS "You want us to be like good Germans, supporting the evils of our decade, and then we refused to be good Germans and came to Chicago and demonstrated; now you want us to be like good Jews, going quietly and politely to the concentration camps while you and this court suppress freedom and truth. And the fact is, I am not prepared to do that." --Peace activist and Chicago Eight defendant David Dellinger to Judge Julius Hoffman during sentencing for inciting a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, 1970 "We, the captive people of the free world of racist America, support the right of all oppressed people to meet violence with violence. We resolutely support the right of all people of self-determination." --Speech by American black activist Robert F. Williams in Hanoi, North Vietnam, 1965 Impulse and speed impel the Knight of Wands forward. As the college professor rushing into a police blockade, angry and barely restrained, Wand fire leads an impetuous charge of muscles and ideas. The probing batons of the officers only irritate the Counterculture Knight, prompting him to argue his points with a battalion of incurious cops. He explains they are tools of an autocratic and corrupt political system. The police want him simply to stand back behind a fabricated line that distinguishes orderly presence from insurrection. The Knight is prone to impatience and high contrast: he assesses events in stark monotones and battles for justice with actions that are brash, naive, and dangerous. There were two Counterculture styles of political resistance that ran through the Sixties. One was guided by the principle of non-violence, a strategy widely credited with advancing the struggle for civil rights. The other was built on the proposition of self-defense, that a people or movement under siege had the right - perhaps even the responsibility - to, in Williams' words, "meet violence with violence." In the struggle for inspiration, these tendencies were constantly contested. Each had its champions, Knights that dashed into conflicts waving either's cudgel. David Dellinger was a life-long activist committed to civil disobedience. His non-violent jousts against the Vietnam War put him at odds with the movement's radical fringe. Robert F. Williams, who took up the civil rights cause in the 50s as a black community leader in Monroe, North Carolina, was a quick convert to the power of armed resistance. His determination to defend his neighbors with guns brought him into angry conflict with Martin Luther King and other civil rights moderates. Throughout the Sixties the choice of violent, or non-violent, resistance was an increasingly crucial one. And embroidered into this choice were the details of a life's experience along battlements besieged by repressive sovereignties. Dellinger was a son of privilege, born into a wealthy New England family in 1915. His father knew Calvin Coolidge and a young David Dellinger stayed overnight in the White House. As an opponent of World War II, he spent two years in prison for resisting the draft. Following the war, Dellinger became an outspoken critic of atomic weapons and edited Direct Action and Liberation magazines for many years. As opposition to the Vietnam War grew among college students, Dellinger took a lead role in non-violent protests. In his 50s, Dellinger was an avuncular protest leader, joining with two Roman Catholic priests, Philip and Daniel Berrigan, in supporting draft resisters with demonstrations at local draft boards and induction centers. Dellinger organized the 1967 protest march that encircled the Pentagon. He went to China, and then North Vietnam, securing the release of captured American servicemen. At the age of 11 Robert F. Williams witnessed the ruthless beating of a black woman by police officer Jesse Helms, Sr., father of the late US Senator Jesse Helms. In 1958, as president of the Monroe, N.C., chapter of the NAACP, Williams defended two young black boys ages 7 and 9 accused of sexual molestation for being kissed by a young white girl. Williams then attempted to integrate the city's swimming pool, his peaceful demonstrators drawing gunfire from Monroe's Ku Klux Klan while police officers stood by. Williams responded by forming his own local chapter of the National Rifle Association and creating a Black Armed Guard to defend Monroe's black community from nightly assaults by Klansmen. Under Williams' leadership, black families fortified their homes and trained with rifles. Williams urged the use of advanced weaponry, including machine guns, to defend against Klan attacks. There were as many as 15,000 Klansmen in the Monroe area and Williams' strategy was effective in stemming their attacks on black families. |