|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

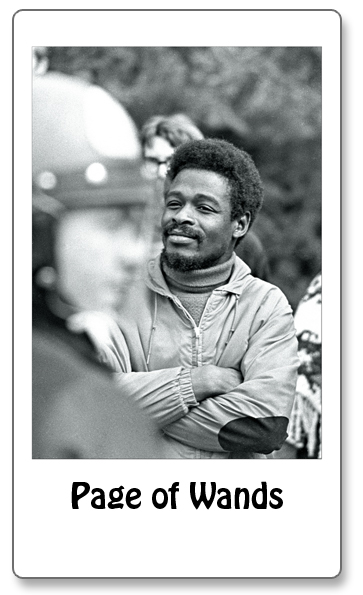

PAGE OF WANDS "So there was a new breed of adventurers, urban adventurers who drifted out at night looking for action with a black man's code to fit their facts. The hipster had absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro, and for practical purposes could be considered a white Negro." --Norman Mailer, "The White Negro" Dissent Magazine, 1957 Associations and traditions follow the Page of Wands, the first member of the Tarot Court. In 16th Century Italy he is Orlando Furioso, the protagonist in Ariosto's best-selling romantic epic of the mad passion and heroic death of Roland, Charlamagne's dearest paladin. Brilliance, courage, sudden anger, obsessive love, ambush, unsettling and immediate emergencies absorb the fleeting, yet perpetual, attachments of the Wands' youngest persona. He (or she) is Aries gone wild, the fire of spring and the pure force of life before it has shape or structure. The Counterculture Page considers with amusement the spectral, encased countenance of his opponent, an Oakland police officer facing thousands of protesters against the Vietnam War. Where did all these angry white people come from? Why are they opposing the cops that for decades had harassed, coerced and beaten the Page's ancestors in the usually unspoken name of white supremacy? The Page recognizes a change in the weather and, in a wily epiphany, embraces it with personal satisfaction. His white brothers and sisters now do some heavy lifting. They quote Malcolm X, they march for civil rights, and they surround an anxious police officer in riot gear as they take possession of the streets. Authorities fear most an opponent with no fear. The Page has no time even to consider if he (or she) is afraid. In Crowley's Thoth deck the Wands Princess never forgets an injury. She shows patience only while lying in ambush to avenge. The Counterculture Page was a school-aged child when in 1957 Mailer wrote the essay in which he presciently describes the source of what he calls the Hip. "It is no accident," he writes in The White Negro, "that the source of Hip is the Negro for he has been living on the margin of totalitarianism and democracy for two centuries." Mailer, in his florid, provocative style, describes the birth of the Hip as a ménage a trios" in which "the bohemian and the juvenile delinquent came face-to-face with the Negro, and the hipster was a fact of American life . . . And in this wedding of the white and black it was the Negro who brought the cultural dowry." In looking ahead, Mailer might have been standing at the corner of Haight and Ashbury as he writes: " . . . Hip may erupt as a psychically armed rebellion whose sexual impetus may rebound against the antisexual foundation of every organized power in America, and bring into the air such animosities, antipathies, and new conflicts of interest that the mean empty hypocrisies of mass conformity will no longer work. A time of violence, new hysteria, confusion and rebellion will then be likely to replace the time of conformity." Mailer's rich, short essay may overstate the cultural bridge from black culture to the Counterculture, but not by much. Whether the Page was a slick-haired youth with collar turned up in 1957 or a shaggy hippie with hair hanging over it in 1967, he shared Orlando's "furioso" or raving passion for living in the present. He was a white Negro and, while not always acknowledging it, at least seemed always to know it. In Wand terms it was black college students who started the student rebellions of the Sixties. Negro America's first large college generation in 1960 began challenging Jim Crow laws in the south by sitting legally, if unwelcome, at Southern lunch counters traditionally reserved for whites. Within a year they were joined by hundreds of white student supporters who stayed on and helped to register black voters in rural, segregated towns and cities. Flocks of white Pages returned to their northern campuses to continue fights for social justice and free speech. Idealism combined with resistance made for intoxicating engagements. As Mailer concluded: " . . . the heart of the Hip is its emphasis on courage at the moment of crisis, and it is pleasant to think that courage contains within itself (as the explanation of its existence) some glimpse of the necessity of life to become more than it has been." |