|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

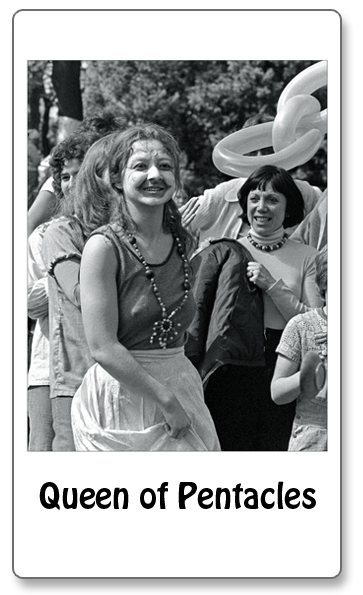

QUEEN OF PENTACLES "In the radical feminist view, the new feminism is not just the revival of a serious political movement for social equality. It is the second wave of the most important revolution in history. It's aim: overthrow of the oldest, most rigid caste/class system in existence, the class system based on sex-a system consolidated over thousands of years . . . To question the basic relations between sexes and between parents and children is to take the psychological pattern of dominance-submission to its very roots. Through examining politically this psychology, feminism will be the first movement ever to deal in a materialist way with the problem." --Shulamith Firestone, "On American Feminism," 1971 She has been likened to Demeter, the Greek's goddess of grain. After the Counterculture's lingering Summer of Love it was the terrestrial Queen of Pentacles who brought in the harvest. It arrived from the era's feminist revolution with fruit that in succeeding seasons continued to fall and replenish the expanding terrain claimed by the women's movement. Even as the New Left collapsed, the Civil Rights movement stalled, and apathy smothered anti-war resistance; even as the Haight-Ashbury crashed and rock singers died, American women found their voices and-with historically astonishing speed over the remaining courses of their lives-a share of power. The Queen of Pentacles is also the huntress Artemis, an ally of Nature whose cunning and strength complement Demeter's sanguine fecundity. Of all the factions once united in resistance during the Sixties, feminists have fought the longest and won the most. It has not been easy, and much of what women want is still contentiously debated and precariously maintained. But across the board of social structures, from politics to the family, from faith to fashion, from vocation to sexuality, from the old schools to the new economies, women-if they have not entirely overthrown what Firestone terms "the class system based on sex"-have greatly endangered its existence. While feminism's seminal Second Wave naturally addressed first the abiding economic inequalities of the workplace, these were quickly recognized as only surface symptoms of a far deeper societal sexism. Women's discussion and protest grew quickly to include such subjects as women's depression, the politics of marriage, media projections of feminine beauty, sexuality, rape, patriarchal coercion, historic repression of the history of women including its centrality to human myth and religion, and linguistic and semiotic representations of the female that implied social and intellectual inferiority. "The cult of beauty in women, which we smile at as though it were one of the culture's harmless follies, is, in fact, an insanity," wrote Una Stannard in her 1971 essay The Mask of Beauty. A decade after the fertile heart of the baby boom, radical feminist Vivian Gornick wrote the following: "The terror of felt sexuality is the terror of our lives, the very essence of our existence. It pervades the culture, but in every aspect of moral law, every nuance of custom, every trace of human exchange, soaking through social intercourse: it is there in restaurants, on busses, in shops, on country roads, and on city streets; in university appointments and government decisions and pleasure trips and the popular arts. Everywhere-like some pernicious covering-can be felt the influence of that fear of the sexual self that has destroyed our childhoods, scarred our adolescences, forced us into loveless marriages, made of us dangerously repressed and corrupt people, and sometimes driven us mad." What other political movement had ever tackled so many issues, especially those tied with deep intimacy to such personal experiences? Because sexism was so pervasive as to be at first blush nearly invisible, women's exploration and resistance was remarkably sensitive and accelerated at the end of the Sixties. Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique had in 1963 given some shape to what she described as "the problem that has no name." By 1971, Germaine Greer in The Female Eunuch was applying sharply descriptive terms to the problem, including very specific analyses of a woman's experiences with society, men, her body, and her humanity. "The first significant discovery we shall make as we racket along our female road to freedom is that men are not free, and they will seek to make this an argument why nobody should be free," she wrote, concluding "The old process must be broken, not made new." Indeed, since sex pervades all social classes, the feminist revolution would not be fought on barricades, but rather in bedrooms, kitchens, and nurseries, graduating inevitably to classrooms, boardrooms, and work halls. Dancing, masked in make-up, cheered by an older "sister" wearing glass pearls, a young woman performs at a women's festival in 1970, surrounded by mothers, children, and balloons. There is obvious pride expressed with her forward steps. The Counterculture may be passing, but the Queen's sheaves still accumulate in the fields. |