|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

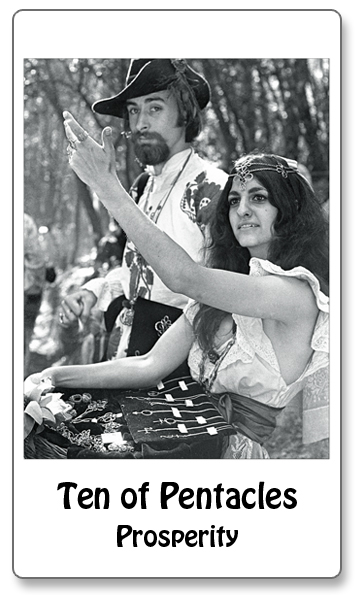

TEN OF PENTACLES "The counterculture excelled at trying a whole lot of stuff in a short period of time. Almost everything we tried either failed hideously or didn't pan out . . . But the counterculture approach to computers-which was of great ingenuity and great enthusiasm, and great disinterest in either corporate or government approaches to their problems-absolutely flourished, and to a large extent created the Internet and online revolution." --Whole Earth Catalogue creator Stewart Brand reflecting on the Counterculture for Rolling Stone magazine, May 3, 2007 We come at last to the promise of physical prosperity that is the earth suit's triumph. Loss of love is deeply felt but it is nothing next to the pain of an empty stomach. Countless generations of humans have struggled to assuage the latter, spending most of their waking time searching for food. Our hunting and gathering ancestors thought of nothing else but in so doing thought themselves into the problem-solving structures evolved within the uniquely adapted human cerebrum. Farming and husbandry grew out of our species' intelligent edacity. With them came the elaborate inlays of culture and, with them, the periodic and perpetual appearance of counterculture. Crowley calls the Ten of Pentacles the Lord of Wealth, "the great and final solidification" of all experiences comprising the Tarot's Minor Arcana. The children of the Sixties grew up in a time of such abundance that it must have seemed there would never again be a fundamental need. Conversations turned on the "affluent society" and its anticipated successor, the "leisure society." So plentiful had wealth become for those in the American middle classes (and above) that some projected the fall of capitalism through emerging economic structures laden with such enormous wealth they would gratefully pay people not to work. Costumed artisans selling their hand-made jewelry in 1967 demonstrate the entrepreneurial energy that surged beneath the Counterculture's initial ideological commitment to free distribution of goods and services. At first the Diggers gave away food and opened free stores. And co-ops were formed to distribute everything from autos to groceries. But the lasting economic paradigms of the Sixties turned on the creation of small businesses, much as the creation of cottage industries in the Middle Ages produced Europe's first merchant class. Economist Michael Phillips, who calls the hippy experience "one of the greatest voluntary experiments in human history," notes that by 1984 hippies had created more than 4,000 businesses in the San Francisco Bay Area alone, "and probably 20,000 more around the country." Some of the products created by hippy businesses didn't last. On a list of hippy failures, Phillips includes water beds, yurts, co-ops of all kinds, barter, local currencies, and composting toilets. But among hippy business successes were innovations in clothing (casual styles including t-shirts printed with social and political commentaries, high-tech and natural fabrics, and recycled clothing), food (organic produce, markets specializing in whole foods, vegetarian restaurants and nouvelle cuisine), health (acupuncture, yoga, meditation, homeopathy, home birth), education (alternative schools and free universities), transportation (rediscovery of the bicycle and the invention of the mountain bike), and social services (recycling, accommodations for the disabled, Meals on Wheels for elderly seniors, hospices, and car pools). Hippies tackled enterprise with playfulness largely foreign to the organization men of their parents' generation. Fundamental to any undertaking was the idea that it should be fun. And for hippies whose businesses were, at least in the beginning, well outside the mainstream (recreational drugs, for instance), fun was attached to a street-smart audacity that comfortably incorporated risk into a business plan. This spirit of fun was on view in 1972 when Stewart Brand, writing for Rolling Stone Magazine, stepped into the Stanford University Artificial Intelligence Laboratory to see a group of programmers and researchers stage an "Intergalactic Spacewar Olympics." Clustered around a time-sharing computer, longhaired graduate students entered commands to shoot down small triangular "space ships" with what Brand described as "frantic delight." A veteran of Ken Kesey's Acid Tests, Brand compared the "out of the body" pleasure of computer hackers to that experienced by dancers at the Trips Festival. "Ready or not, computers are coming to the people," Brand wrote. "That's good news, maybe the best since psychedelics." |