|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

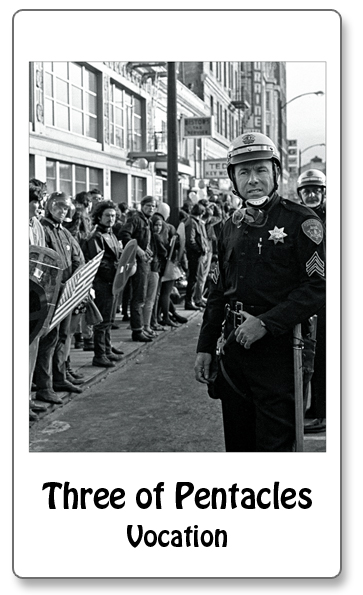

THREE OF PENTACLES "Although the '60s counterculture has been much maligned and discredited, it attempted to provide what we still desperately need: a spirited culture of refusal, a counter life to the reigning corporate culture of death. We do not need to return to that counterculture but we do need to take up its challenge again. If the work we do produces mostly bad, ugly and destructive things, those things in turn will tend to recreate us in their image." --Curtis White, "The Spirit of Disobedience: An invitation to resistance," Harper's Magazine April 2006 The Three of Pentacles covers the terms of employment. It is, in the Rider Waite card, a priest and architect attending the construction of a Gothic cathedral, offering their thoughts to a mason who dutifully applies them. In our world it is the apprentice on the job site and the manager in the mailroom. But as much as work itself, the Three of Pentacles proposes the realizations of our labor. Work for most of us is the central material reality of our passing days, raising sometimes troubling questions about the quality and meaning of our cumulative lives. Are we engaged with a job-or a vocation? As White says, if the work we do "produces mostly bad, ugly and destructive things" we may be pushed into a painful moral conflict or, worse, simply benumbed by trappings that are only briefly pleasing plums of occupational enslavement. Forty years after the Counterculture, essayist Curtis White closes his harsh critique of modern America ("..the empire that the rest of the world reads in George Bush's smirk") by pining for a return of the "culture of refusal." The Counterculture quality most praised by Curtis was the celebrated and conscious choice to refuse work offered by "the reigning corporate culture of death" and, instead, to oppose it. Many in the dominant culture of that time disdained what they perceived as a shiftless shirking of responsibility by young adults, especially college students who bore a presumed "investment" from their society's capitalist benefactors and who should therefore return that investment with compliant employment. But those in control (captains of industry, politicians, and parents) did not then understand that to "refuse" was also to work. To resist a death culture, its wars, its institutionalized bigotry, its tightly managed factories of learning, was to be meaningfully, if not gainfully, employed. The flummoxed police officer in the street in front of the Oakland Induction Center in 1967 is doing his job. But the anti-war protestors he faces believe strongly they are doing their duty-a different kind of work that binds labor to a vision of justice. Sixties writer and historian Theodore Roszak was most intrigued by the youth of his era's Counterculture, and how widespread the spirit of refusal extended among a very large generation of near children. What did youth possess that led them to "refuse" so effectively and affirmatively the corrupting commands of the dominant culture? Roszak, however, asked a better question: what did they not possess? For one, "they had been given no taste for the rigidities and self-denials that adulthood is supposed to be all about," he wrote. "General Motors all of a sudden wants barbered hair, punctuality, and an appropriate reverence for the conformities of the organizational hierarchy. Washington wants patriotic cannon fodder." These had no appeal to a generation raised through the longest adolescence in history, whose entitlements of pleasure and fervid imaginations had been well bred beyond the boxes prescribed by society. The young, said Roszak, were up to nothing less than a reorganization of the prevailing state of personal and social consciousness. They even disregarded the moralizing of older leftist mentors who could not seem to understand that when one raises the question of what a person really is, the politics of the social system yield quickly to what Alan Watts calls the "politics of the nervous system." Whatever a person is, the Counterculture was committed to the realization of that person's unrestricted joy. "The hippie, real or imagined," concluded Roszak, "now seems one of the few images toward which the young can grow without having to give up the sense of enchantment or playfulness." The spirit of refusal has been practiced by a generation, if not always in its public lives, quite often in private ones. Refusal is always available to defy social injustice, but also-as feminism and the civil rights movement made clear-essential to fending off private harm and abuse. There is no need to be young to have a direct experience with the world. But it does seem important to think you are. Nothing is more youthful than a vivid and resonant imagination. |