|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

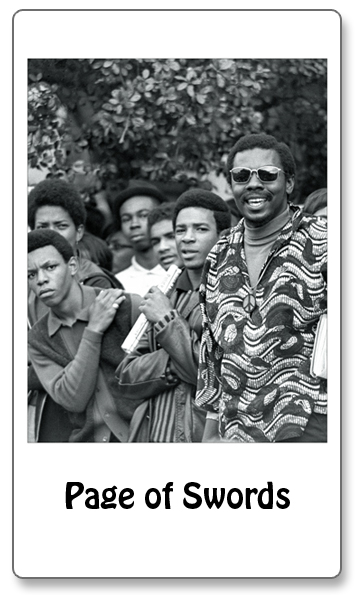

PAGE OF SWORDS "As for white America, perhaps it can stop crying out against 'black supremacy,' 'black nationalism,' racism in reverse,' and begin facing reality. The reality is that this nation, from top to bottom, is racist; that racism is not primarily a problem of 'human relations' but of an exploitation maintained . . . either actively or through silence . . . by the society as a whole. Camus and Sartre have asked, can a man condemn himself? Can whites, particularly liberal whites, condemn themselves? Can they stop blaming us, and blame their own system? Are they capable of the shame which might become a revolutionary emotion?" --Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader Stokely Carmichael from "What We Want" 1966 The young Page of Swords swings his weapon wildly at the sky, chopping at collocations of clouds as if to bring down the order of the heavens. The Page is vigilant and alert, but the clouds are too ephemeral to pose a threat, and in any event were never his enemy. It is characteristic of the Page that he is challenged by anything that moves. He is old enough to feel danger and strong enough to defend, but still not always certain what threats are real. By 1966 the Civil Rights Movement in America was a decade old, but progress still seemed hard to measure. There were many successes. There were also setbacks and a formidable white resistance to racial equality. Martin Luther King Jr. still led non-violent marches to desegregate communities, protests that drew the support of many whites. But a younger group of black activists was becoming increasingly impatient and weary of non-violent action that seemed only to draw ever more violent responses from reactionary racists. "For too many years, black Americans marched and had their heads broken and got shot," said Stokely Carmichael, SNCC coordinator who led successful voter registration drives in the South. Carmichael and other young leaders like H. Rap Brown had first-hand experience with the repressive violence of white separatists and heard in the expression "black power" a succinct promotion of self-defense and cultural pride. In June James Meredith, the young black student who in 1962 fought a legal battle to successfully integrate the University of Mississippi, organized a "Walk Against Fear" to Jackson. But when a white racist shot Meredith in Memphis, civil rights leaders rushed in to save the march. Along the way in Greenwood, younger marchers began to chant "Black Power! Black Power!" While members of Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference tried to shout them down with cries of "Freedom Now!" they couldn't smother the new chant that was filmed and played back that night on national news. When NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins called Black Power "the father of hatred and the mother of violence" he cracked open the Civil Rights Movement's generation gap. At the other end were young college students like those pictured here, members of the UC-Berkeley Black Student Union (BSU) holding its first rally in the autumn of 1966, its confident spokesman sporting a dashiki, a West African garment that would become increasingly fashionable as Black Power spread its wings. "Black is beautiful" was a popular and positive expression of the widening movement that stressed in a single phrase the emergent cultural and political awareness of African-Americans. A generation of defiant Pages came forward, staffing groups like the Black Panther Party with young soldiers, almost all between the ages of 15 and 25. Militant Panthers were particularly bold, harassing the police that patrolled West Oakland neighborhoods by tailing them, rifles at the ready. The Panthers were a popular and charismatic force. Dressed in leather jackets, black trousers and black berets, they presented a formidable sight at rallies and marches. Within a year the Panthers had become a national organization with more than 2,000 members in several large cities. In 1968 Black Panther Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver ran for President on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket and received 200,000 votes. In the Sixties Black Power spurred a youth movement of impatient vigilance imitated by other emerging factions of the Counterculture. Ethnic groups comprising Latino, Asian, and Native-American college students formed their own activist political organizations. The Women's Liberation Movement found inspiration from Black Power. "Women began to 'rap' (talk, analyze in radical-ese) about their essential second-classness," wrote Gloria Steinem in 1969, "forming women's groups in much the same way Black Power groups had done." |