|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

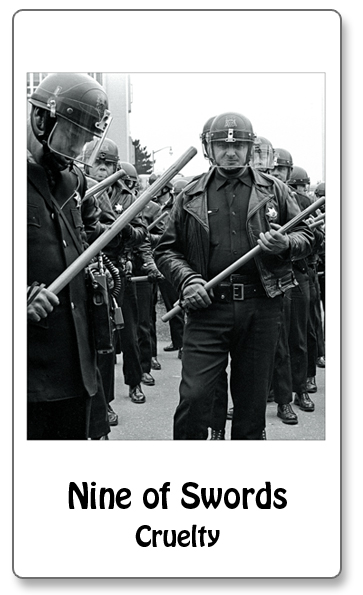

NINE OF SWORDS " . . . all of them except James Black were handcuffed and driven to the Lowndes County Jail. Black was left with patrolman Elders. At the jail about twenty minutes later, James Black came in with Elders. Black's head was dirty; one side of his face was swollen out of shape. His clothes were torn and disarranged. He walked up to me and said, "He beat me," pointing to Elders. Elders said, "This boy fell getting out of the car" (shortly thereafter Sam Block was taken outside, and we could hear sounds of beating and groans.) He said Block was brought back to the cell, holding his sides, his mouth swollen . . . Block in his affidavit quoted the jailer as saying, "The river is just right; let's carry them out and rifle them right now." --Affidavit of voter registration volunteer Charles McLaurin describing police brutality in Columbus, Mississippi, June 8, 1964. Love may be the song it sings, but callous cruelty was the Counterculture's political crucible. The Nine of Swords brings the suit's most confounding agony: an inhumane resistance to the most human of rights. In the Sixties this resistance formed quickly around efforts to exercise civil liberties, to redress grievances, and to challenge authority. It's most despairing and acrimonious presence was felt in confrontations with police forces that stood in for civilian defenders of repression, bigotry and changeless tradition. It was in the South that these struggles first emerged, and it was from the South that the Counterculture learned to mount its broader public opposition to racism and war, one that produced an inevitably broader collision with law enforcement. There is a thin line between force and brutality, one often indistinguishable to a police officer left in the street not just to enforce the law, but also to express the sovereign community's outrage at those who defy its customary primacy. And in most instances police gladly played the role of enforcer, legal or otherwise, of the status quo. Embodied in this severe Nine are hard judgment, rigid attitudes, and orthodoxy. Arising from this card, as A.E. Thierens has written, are "inquisition and every sort of intolerance." In Selma, Alabama, lived some 15,000 black residents old enough to vote; yet in 1964 only 130 were on the county voter rolls. As civil rights workers tried to register black voters they were harassed, arrested, and beaten by local sheriff's deputies and police. On February 18, 1965, state trooper James Fowler shot Jimmie Lee Jackson in a café where he and his family had fled during a civil rights demonstration. Jackson died eight days later, sparking a march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery to protest the killing. As 600 peaceful marchers arrived at the Edmund Pettus Bridge six blocks away, state troopers and police, some mounted on horseback, attacked them. The police used billy clubs, tear gas, and bullwhips to drive back the marchers. The violent, unprovoked police attack was captured on film and televised nationally, arousing strong support for the civil rights movement. Seventeen marchers were seriously injured and hospitalized. The day is remembered as "Bloody Sunday" and it was a watershed in exposing police violence directed at black citizens who tried to exercise their rights. The Detroit Riots of 1967 began when police vice squad officers raided an after-hours bar on Twelfth Street. White officers frequently harassed black residents in the Twelfth Street neighborhood, stopping black youths to call them "boy" and "nigger." In the early Sixties police were responsible for the murder of one prostitute (shot in the back) and the severe beating of another. Black teenagers suffered frequent beatings at the hands of white cops. Black Detroit residents consistently identified police brutality as the number one problem they faced. During the police raid on the 12th Street bar, officers found more than 80 patrons celebrating the return of two Vietnam veterans. While police began to make arrests, a crowd formed outside. When the last police car left, a small group of men lifted the bars from the windows of a nearby clothing store and broke in. Vandalism began to spread through the Northwest side of Detroit, and then crossed over to the East Side. Within two days the National Guard and Army were battling residents in the streets as police and troops struggled to regain control of the city. After five days of rioting, 43 residents were dead, more than 1,000 were injured and 7,000 people had been arrested. One of the dead was a four-year-old girl, killed when the National Guard sprayed an occupied apartment building with a tank's .50-caliber machine gun. These two outbreaks were among hundreds of civil disturbances that occurred in America and around the world during the 1960s. And in most all, as historian Arthur Marwick notes, "there can be no question that throughout the decade almost all instances of violence and rioting came into being because of the insensitive (or worse) behavior of the police."s Whether they were sheriff's deputies in Chicago, French gendarmes in Paris, or Italian Caribinieri in Rome, they brought their guns and clubs into confrontations with students and minorities and made good use of the ensuing confusion to inflict great harm and occasional death. |