|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

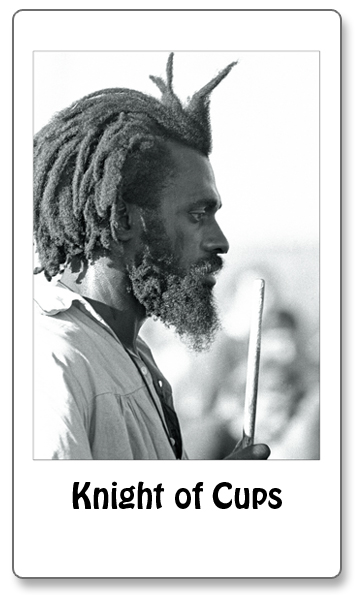

KNIGHT OF CUPS

"Oh God said to Abraham, 'Kill me a son'

--Bob Dylan "Highway 61 Revisited" from the album of the same name 1965 "Turn off your mind relax and float down-stream, it is not dying, it is not dying . . . " --The Beatles, "Tomorrow Never Knows" from the Revolver album 1966 The Knight of Cups writes the songs. The Knight has grown beyond the infatuated Page and now invigorates in supple articulation the full range of his emotions. He rides rhythms bareback and conjures out of an ether of words and sounds the heartbeat's soaring spirit. He is, like the drummer here swinging his lance, a source of experience, a shaman channeling a mystical embrace in which music and lyrics serve as psychic symbols of healing, individuation, integration, and self-actualization. It is impossible to address the ocean of feelings that emerged out of the Sixties without acknowledging the vast and deep impact of music. Indeed, music's lyrical explorations of newly aroused realities complemented the era's embrace of new forms of consciousness, particularly those inspired by the psychedelic experience. Music was more than a soundtrack or an entertainment. It was in its more fully realized innovations a mystical trigger of psychic and physical animation. The Counterculture Knight was the musician. And it seemed that every young person wanted to be one. Acoustic guitars were everywhere in the early Sixties and as a folk music revival drew audiences weary of bubble gum rock, but still hungry for an authentic bluesy sound, the Western world seemed on the verge of some new musical discovery. The first folk rock song is widely acknowledged to be the 1965 hit "Eight Miles High" by the Los Angeles group The Byrds. And the first tune to feature the word "psycho-delic" was a 1964 version of "Hesitation Blues" by a pre-Fugs New York group called the The Holy Modal Rounders. But these are footnotes in the astonishing rise of folk and psychedelic rock in the mid-60s, forms that were defined and dominated by the prolific, eclectic, and wildly creative music of folk artist Bob Dylan and the English group first known as the Quarrymen and later called the Beatles. Each produced a unique sound and lyric that in their different ways linked similarly to what Nick Bromell describes in his Sixties musical history Tomorrow Never Knows as "the legitimization of this adolescent vision of life as a river of change . . . undertaken first through rock n roll and later through psychedelic drugs." Dylan told his musical fables like a modern troubadour and the Beatles projected their at times orchestral fantasies in ways that probed current questions of identity and reality, as well as the consequential choices that defined them. Throughout the 60s the Beatles and Bob Dylan reigned as royalty, the supreme Knights whose fruitful musical oeuvres connected not just with our musical tastes, but with the cortical centers that formed our senses of self. Each produced albums eagerly awaited, examined and discussed; that were engaged as experiences co-equal with emotional reality, and that were memorized and retained as liturgies of the Counterculture. More than other Counterculture Knights, Dylan and the Beatles seemed to grow up by our sides, seemed to pass through the same crucibles and cross the same fields, have coincidental mystical realizations, and offer back the qualities of these experiences in their enveloping words and sounds. Lyrics became homilies for the ages: "He not busy born is busy dying" (Dylan) or "The love you take is equal to the love you give" (The Beatles). |