|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

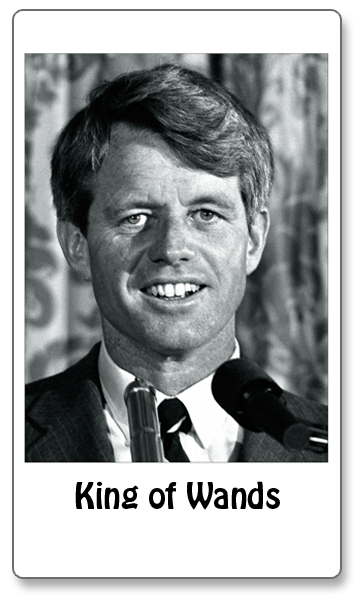

KING OF WANDS "My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: 'In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God. What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness, but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black." --Robert F. Kennedy, speaking after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., April 4, 1968 Compare the King of Wands to The Fool: both are energetic, but one expresses responsibility and the other pure instinct and freedom. Those who presumed that Bobby Kennedy's candidacy for the presidency in 1968 would lead the New Left's revolution (even as Kennedy rhetorically called for one) did not comprehend the context of his experience and his commitment to all Americans. At age 42, as young as he was, Bobby Kennedy was not an activist. He was not a hippie. And the tradition he represented was one of sacrifice, patience, negotiation, a traditionally religious faith in God, and an ecumenical optimism that people with diverse, even opposing, interests and desires could live together. Yet in 1968 he was the Counterculture's only political salvation. Even as the New Left's Movement recognized that it was just a sliver of Kennedy's constituency, it knew that no other national leader would even acknowledge the forces of rebellion in the streets. After the murder of Martin Luther King, Kennedy was the only national leader who could effectively challenge the cynical brokering of the Presidency. Kennedy's unequivocal anti-war stance defied the incumbent President of his own party and struck a defining contrast with the likely Republican nominee, Richard Nixon. Like a mythic ancient, Kennedy carried on his shoulder a raven of death, prepared to enter the Orphic mysteries vulnerable to the risks that offer rebirth. The murder of his own brother/President, friends later wrote, had changed him deeply. As he said in his urgent appeal to the nation after Dr. King's death: "For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man . . . But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land. Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and to make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people." Four days before his own assassination on the night of the California primary election, Kennedy stood before the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco. He was sprinting through the campaign's last days. Recent polls showed him moving into the lead over anti-war candidate Gene McCarthy. A victory in the nation's largest state would put the wind at his back heading toward the convention in Chicago in August. And when he won the primary on June 5 it seemed momentarily possible that Kennedy could win the nomination. And what would that have meant? Could a Robert Kennedy presidency have ever become a reality? What if the King of Wands had become the leader of the nation? It is a question that has spurred speculation and hopeful fantasy for more than 40 years. |