|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

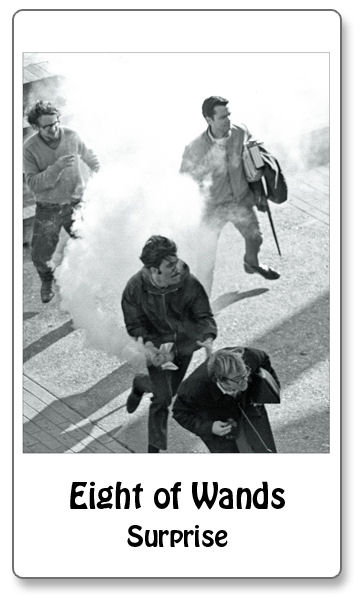

EIGHT OF WANDS "Perhaps he has no choice and he is pure fatality; perhaps there is no fatality and he is pure will. His position may be invincible, absurd, both or neither. It doesn't matter. He is on the scene." --Carl Oglesby, President of Students for a Democratic Society, 1965-66, describing the Sixties revolutionary The Eight of Wands sends sticks flying. It is the messenger of swift action and fire beyond combustion. It is a mercurial flame and, in the Thoth Tarot, comparable to pure light or electric current. It is the shock of the new before its inevitable reverberation. In 1969 Time magazine published an article looking back at the Sixties. From that tumultuous decade it pulled two surprises: the common appearance of obscene language and outrageous dress and behavior, and an unprecedented rise in public violence. Time credited both surprises to a generation of "new romantics who scorned gradual reform; for them it was Freedom Now, Peace Now . . . Utopia Now." The student rebel here, hurling back a police teargas canister, could have stood on the barricades of Paris in 1848. Things happened quickly in the Sixties, nothing more quickly than street warfare that pitted activists and revolutionaries against soldiers and police. But romantic radicals weren't the only ones to take to the streets. In France, workers supported a student-led revolt that in 1968 nearly overthrew the government. Beginning with the Watts riots in Los Angeles in 1965, American cities were wracked periodically by anarchic violence as crowds of black residents, prodded by police brutality, racism, and poverty, exploded in a destructive rage that took many more lives and did far more destruction than any student protest. As SDS leader Ogelsby famously stated in his speeches and writings: "It isn't rebels who cause the troubles of the world; it's the troubles that cause the rebels." Oglesby's canister-throwing revolutionary may be invincible or absurd or neither. But he is always moving. Aleister Crowley named the Eight of Wands "interference" and thought it represented high-energy physics. Motion at the nuclear level is the way particles increase velocity with the application of energy and fly off everywhere. Likewise, the Sixties experienced its own atomization, a break-up signified by the increasing number of interest groups with similar ideals but little or no consensus of aim or desire. The break-up that eventually pitted feminists against the New Left, that isolated radical blacks from sympathetic white supporters, that marginalized moderate liberals who could not accept Marxist truth, made for unstable alliances. Speed moved things forward, but so much could not keep up. Arriving at change with a critical mass was an elusive achievement. It happened occasionally at big demonstrations and large rock festivals. It was notable at the Human Be-In and revisited during a March on Washington. As represented by the Three of Wands, the capacity to mobilize was one of the Movement's strengths. But its whipsaw ideological dialogue frequently obscured goals in a muck of cantankerous process. And by 1969, when SDS was taken over by a cadre of young, but surprisingly doctrinaire, terrorists, the Movement had sped full circle: from its roots at the alienated edges of the 20th century's progressive politics, through a large and creative generation of visible and idealistic leverage, and then back again to the alienated outlaw status of anarchistic bomb-throwers. At that point much of the Counterculture, especially its peace-loving hippies, lost interest. |