|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

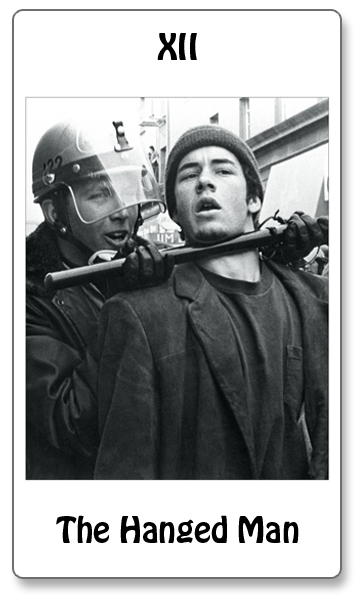

THE HANGED MAN "For years now I have heard the word 'Wait!' It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This 'wait' has almost always meant 'never.' We must come to see with the distinguished jurist of yesterday that 'justice too long delayed is justice denied.'" --Martin Luther King, Jr. Letter from Birmingham Jail April 16, 1963 The Hanged Man embraces enforced inactivity, the bane of the Western mind. On a traditional card he hangs upside down, strung by one foot from a gibbet, his head inverted and sometimes suspended over water. It has the look of torture. In medieval Italy, presumed birthplace of the modern Tarot, it was a punishment for traitors to hang, helpless and humiliated, by their feet. Certainly the protester here has been suspended by the menacing police officer behind him. Our Hanged Man appears momentarily flummoxed while the cop grins assertively. He has become a prisoner, his motion suddenly and ignominiously limited, while the act that brought him here was one of determined and direct action. Yet seen another way, the suspended animation of the Hanged Man is a blessing, a vital pause in the course of existence. Immobility may at first feel excruciating and humiliating. But within its subsequent despair are born reflection, humility, and affirmation. Were there any who lived through the Counterculture without at some time finding themselves stuck, trapped in involuntary contemplation of a dilemma, saddled with "hang-ups" that could only be addressed through some enforced sanctuary? Certainly tens of thousands of protestors volunteered to be hanged, to resist war or racism by clogging jails and prisons. It was during a hiatus in jail that Martin Luther King wrote his powerful letter to timid fellow ministers in Birmingham, expressing with beatific clarity the need for civil disobedience in the struggle for civil rights. Not all who arrived at the Hanged Man's scaffold were seekers. Many arrived unconsciously, accidentally. Soldiers on their way to Vietnam did not intentionally seek the disturbing epiphanies that later accompanied them home, especially those who were left immobile (and hanging) by mental illness or physical injuries. For those lucky enough to survive, wastelands of death and destruction are always rich with humiliating trials of personal discovery. Thousands of these Hanged Men returned from the war. One was Ron Kovic who served two tours of duty in Vietnam before bullets to the spine left him paralyzed from the chest down. He became one of the nation's best-known peace activists, leading groups of Vietnam Veterans in wheelchairs on protests and hunger strikes. A warrior who refused to go to war was World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Muhammad Ali. Ali had converted to Islam, changing his name from Cassius Clay. In 1967 Ali refused to step forward when his name was called at the U.S. Armed Forces Induction Center in Houston. "I got no quarrel with them Viet Cong," said Ali. "They never called me nigger." Ali was stripped of his title and convicted of draft evasion. He spent four years suspended from a gibbet before his conviction was overturned and he could fight again. In April 1968 Esquire Magazine featured on its cover a manipulated photo of Ali in his boxing shorts, posed as the Christian martyr St. Sebastian (another archetypal Hanged Man), tied against a wall and pierced by arrows. Women also struggled with the immobilizing gulf that exists at the threshold of change. Much of the Counterculture was suffused by the issues that exploded out of the entrapment of women that Betty Friedan first described as "the problem that has no name." Wrote Friedan in as lyrical a description of The Hanged Man as there ever was: "The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night - she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question - 'Is this all?'" Friedan visualized millions of women tied to gibbets of tedium, stretched out like inverted dancers as they lay beside their husbands while pondering a curiously comfortable but unsettling confinement. And in the years that followed, her eloquent description provoked many names for the problem with no name. |