|

| Journeying the Sixties: A Counterculture Tarot |

|

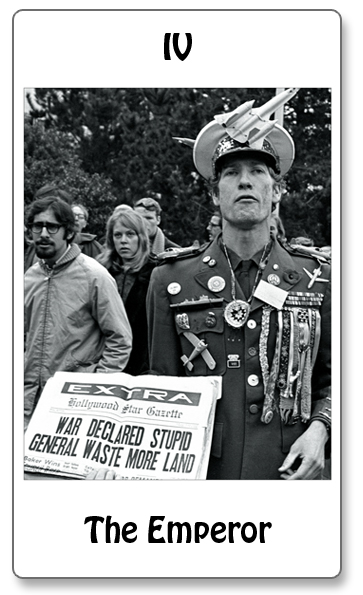

THE EMPEROR " . . . it must be for a good and profound reason that virtually every aware person can remember exactly where and when he or she heard the dread news of November 22, 1963. John F. Kennedy had been relatively young, his death untimely in the extreme. The educated young felt his call, projected their ideals onto him. His murder was felt as the implosion of plenitude, the tragedy of innocence. From the zeitgeist fantasy that everything was possible, it wasn't hard to flip over and conclude that nothing was." --Todd Gitlin, "The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage" The 1960s began with an Emperor whose fabled court was called Camelot after the Arthurian legend (and popular Broadway musical). But the assassination of President John F. Kennedy brought America a succession of Fisher Kings, wounded leaders tormented, as they also are in the old Grail legends, by incurable wounds. More than their wounds was the sickness they aroused, and which spread from the wounded kings to their wounded nation, turning it into a vast, angry wasteland. Kennedy's death was a shock that recoiled out of every television set in the world to become an indelible shared memory, a new archetype birthed like an angry god from the blue glow of a burning tube. Four days of televised coverage during a cold November weekend in 1963 included the live assassination of Kennedy's assassin. We were a country morphed suddenly from stable confidence into a people fed for days on the adrenalin of a bad dream. In the wake of its vivid primetime violence, the riderless horse behind the President's hearse (boots backward in the stirrups) symbolized the leaderless dearth of the next decade and, some might say, all the decades thereafter. Where was the Emperor during the Counter culture years? There wasn't one. This image shows us General Waste More Land, a protester's costumed parody of President Lyndon Johnson's Army Chief of Staff, General William Westmoreland. It was Westmoreland's incessant requests for more American troops that pushed Johnson into a winless swamp in Vietnam. A graduate of Harvard Business School, Westmoreland was a technician of war and sold it as if he were selling futures. His incremental build-up went almost unnoticed until so many bodies were coming home that Life Magazine produced a cover article on one week's American war dead, running photos of each soldier and telling each brief, sad story. "The Oriental doesn't put the same high price on life as does a Westerner," Westmoreland said in 1967. It was widely recognized as a racist justification for the indiscriminate killing of Vietnamese. But it was also a confession: Westerner Westmoreland's war sent more than 50,000 American coffins home between 1964 and the war's dismal end in 1973. The value of human life meant nothing to Westmoreland if it stood in the way of victory. And it did. Westmoreland tried to fight a war of attrition without recognizing the obvious obstacle: there were more Vietnamese in Vietnam than Americans. |